The Stylistics of Olfactory Art as an Idiolect of the Atmosphere

Madalina Diaconu

“How can social critique and emancipatory aims be incorporated into the phenomenology of the atmosphere? How can art spaces be adapted to host exhibitions on olfactory art? It is obvious that far from being complete, the aesthetics of atmosphere need to be set forth and adapted to specific fields of application, including olfactory art.”

Volume Two, Issue Two, “Senses,” Essay

Carleton H. Graves, Coffee plantation showing the berries, Jamaica, Gelatin silver print, 1899. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Source.

The man pictured here shows the plump cherries of a coffee plant while surrounded by some of its last fragrant, white blossoms. The typical coffee drinker won’t usually mull over the process of cultivating these fruits for bean production as they inhale their favorite roast. Likewise, the colonial history of the exploitation of people and land as a result of the coffee trade is typically forgotten in the consumer’s olfactory experience. What can aromas reveal through atmospheric, aesthetic mediums? As Madalina Diaconu illustrates in a pertinent example using Peter de Cupere’s Stay Awake (Coffee Room Installation), olfactory art—when explored through rhetorical terms—can bring materiality and affectivity to the fore. The caption of this photograph, “Coffee plantation showing the berries, Jamaica”, could be read as a synecdoche; the man and berries stand-in for the coffee plantation itself, whereas the plantation workers are not seen. What metaphors can aromatic atmospheres evoke? Diaconu’s insightful pairing of rhetoric and the sense of smell recasts conventional approaches to olfactory art within the philosophical aesthetics of atmosphere.

- The Editors

Both olfactory art, defined as the art that uses odorous substances or alludes to smells, and the aesthetics of atmosphere, which focuses on emotional ambiances, are rather recent phenomena. In 2007, Larry Shiner and Julia Kriskovets claimed that olfactory art “is still in its infancy,”1 and in 2020, Shiner still argues that olfactory art deserves to be taken seriously, in spite or maybe precisely because of the challenges it poses to aestheticians and art practitioners.2 Whereas olfactory art only occupies a niche within the art establishment, the aesthetic theory of atmosphere is now rapidly spreading in international circles, although its philosophical basis was established thirty years ago. Given the polymorphism of olfactory art on one hand and the imprecision of the concept of atmosphere on the other, it is imperative to clarify the relationship between them. A brief introduction to the phenomenological aesthetics of atmosphere will show that the concept of atmosphere is mainly used by scholars to describe emotional spaces, and air qualities are only mentioned incidentally. Moreover, the aesthetic category of atmosphere or ambiance challenges the ontology of things, resists analysis and blurs the conventional distinctions between subject and object, description and evaluation, as well as cognition and affectivity. Although the founder of the aesthetics of atmosphere, Gernot Böhme, rejects the logocentric tradition, that is, the primacy of semantics and interpretation in the philosophical aesthetics, I argue that linguistic terminology and rhetorical tropes in particular help us to better understand specific olfactory works of art, installations and interventions. After detecting the figures of speech that underlie selected olfactory works by Clara Ursitti, Peter de Cupere, Meg Webster and Valeska Soares, this paper examines the direct use of language and verbal metaphors in olfactory art. The last section reinterprets the concept of idiolect (an individual’s personal language that includes lexical, stylistic and rhetorical features) as a specific set of expressive means; various arts employ specific “idiolects” or “languages” in order to create ambiances, olfactory art being only one of them.

The Rise of Atmospheric Studies

The past few years have recorded a significant growth in the atmospheric humanities in several disciplines, from literary studies to media, film and theatre studies, and from architecture and design theory to economic psychology. The first theoretical examinations of the atmosphere (Fr. ‘ambiance’), however, were authored by German phenomenologists, and only the English translations of their work produced during the last decade have allowed for the international breakthrough of this approach. At present, it is even possible to diagnose the beginning of a third wave of the aesthetics of atmosphere, after the German and the European wave, characterized by the emergence of cross-cultural approaches.3

The phenomenological notion of atmosphere was first used in 1964 by Friedrich Otto Bollnow in a pedagogical context.4 Five years later, Hubert Tellenbach integrated it into his phenomenology of the “oral sense” (which includes the olfactory and the gustatory senses) and applied it to psychology, psychiatry, and literature.5 At about the same time, the founder of New Phenomenology, Hermann Schmitz, reinterpreted the concept of atmosphere as an emotionally-tuned space.6 However, groundbreaking for today’s boom of atmospheric studies was Gernot Böhme, who in the 1990s took over the concept of atmosphere from Schmitz and linked it to the Heideggerian notion of Befindlichkeit (mood), considered a specific category of the human existence (Dasein).7 Having this strong phenomenological tenet in the background, Böhme is one of the pioneers who redefined the aesthetic theory as aisthetics (i.e. theory of perception). Moreover, he introduced completely new categories that were meant to provide an alternative to the traditional primacy of language and semantics in aesthetics, such as atmosphere (Atmosphäre), the atmospheric (das Atmosphärische), mood, synesthesia, scene, and ecstasy.8 The following expansion of the theory of atmosphere and the diversification of its subjects encouraged Christiane Heibach to classify the atmospheres into primary or physical-climatic, secondary (social), and tertiary atmospheres (in the media).9 The best-known Italian theorist of atmospheres, Tonino Griffero, notable for his intensive translational work and book series on atmospheres,10 assigned a universal character to the atmospheres. Their ubiquity probed him, in 2014, to speculate about the emergence of a new discipline called “atmospherology”; its tasks would be to clarify the ontological, epistemological, medial, social and aesthetic dimensions of the atmosphere.11 It is also important to acknowledge the accomplishments of the International Ambiances Network.12 Launched in 2008 by a small group led by Jean-Paul Thibaud in Grenoble and Nantes, the network has since been growing, organizing congresses, and editing journals with international participation. Its profile is multidisciplinary, yet with a clear focus on architecture, urban planning and design. These initiatives have significantly contributed to the rapid expansion of the aesthetics of atmosphere in the academic world, as have more general scientific and social factors, such as the emotional turn and the transition to an “aesthetic capitalism.”13 Finally, it is worth mentioning that the concept of atmosphere presents specific affinities with other influential theories in German speaking countries, such as Peter Sloterdijk’s monumental Spheres trilogy14 and Hartmut Rosa’s existential interpretation of resonance.15

Theoretical and Methodological Challenges of the Atmosphere

While atmospheric feelings, mainly a mixture of confused fear and ecstatic entertainment, seem to capture the spirit of our age, the notion of atmosphere poses at the same time remarkable challenges to its philosophical theory. It is not only the polysemic concept of the atmosphere which remains vague, but the phenomenon itself is diffuse. Already Hubert Tellenbach pointed out in 1968 that atmospheres are integral units that resist analytical approaches and push the descriptive function of language to its limits.16 The very definition of atmosphere requires clarification; Schmitz, for instance, characterizes the atmosphere as “a total or partial, in any case considerably broad occupation of a surfaceless space in the field of what is experienced as present.”17 Paraphrasing Schmitz, Griffero presents the atmosphere as “a qualitative-sentimental prius, spatially poured out, of our sensible encounter with the world.”18 Put plainly, atmospheres generally refer to emotional spaces (Gefühlsräume), localizable moods, or affects which are poured out into a space, so to speak. The fundamental debate as to whether atmospheres are merely subjective projections into space or, on the contrary, external, almost elementary “forces” that overwhelm the subject, is still open. Böhme preferred a moderate answer to this question and characterized the atmospheres as being relations “cum fundamento in re”; this means that the evident feeling of an atmosphere must have an objective correlate in specific qualities of things, otherwise we could neither have the experience of entering an affectively-tuned space, nor be aware of the discrepancy between our own mood and the atmosphere emanated by an environment.19 Moreover, he distinguishes between atmospheres (Atmosphäre) and the category of the atmospheric (das Atmosphärische); the latter refers to physical events and states, such as a storm or darkness, that constantly evoke specific moods. The atmospheric corresponds to a first stage in the objectification of atmospheres, a fact which entitled Schmitz and Böhme to also call these phenomena “quasi-things” (Halbdinge).20 Atmospheres, however, in Böhme’s approach, occur before any separation between the subject and the object, and their experience requires the physical presence of a corporeal individual subject in situ. This double focus on presence and corporality explains the genealogy of the aesthetics of atmosphere in phenomenology. Nevertheless, the presence of atmospheres in a space can no doubt be collectively felt; the “sense” of atmosphere or the sensitivity towards what lies, so to speak, in the air may be uncommon, but it still allows for intersubjective judgments.

In general the theory of atmospheres is confronted with internal tensions and specific paradoxes. For example, the dynamics and situational dimension of atmospheres counter the traditional primacy of the classical ontology of things in the Euroamerican world; atmospheres are more like qualities and “events in which action and effect coincide.”21 In addition, scholars commonly emphasize the immediacy of atmospheres; in this respect, the phenomenology of atmospheres performs a specific shift in understanding the subject, by moving away from an intentional and conscious agent (Germ. Akteur) toward a passive subject (Patheur) who is affected by what s/he contingently runs into.22 As a matter of fact, our experience of atmospheres is in practice influenced by both cognitive input and moral values which relativize their aforementioned immediate dimension. In a similar way, atmospheres are in principle holistic, indivisible units, but de facto they can be – at least partly – purposefully designed in architecture, on stage or in film by composing specific elements, such as light, sound, warm or cold materials, loud or intimate music, etc.23 It would outreach the scope of the present paper to raise all the questions that are still awaiting an answer in the aesthetics of atmosphere, yet let me briefly mention just a few: does the ascription to atmosphere to a situation or place have a neutral, purely descriptive meaning, or does it imply an aesthetic evaluation, so that the atmospheric quality would resemble the “flair” in tourism promotion and implicitly refer to a positive value? Is the quality of being atmospheric gradable? From an informative perspective, this would mean that we simply experience some places as being more atmospheric than others; as an aesthetic statement, this would imply an appreciation of some atmospheres as being more valuable than others. Furthermore, what are the possibilities and limitations of new media in staging atmospheres? What is the relationship between the atmospheric design on one hand and consumerism, eventification, or the “experience society” (Erlebnisgesellschaft) on the other hand, a concept which Gerhard Schulze introduced in 1992, simultaneously with Böhme’s “turn” to the atmospheric?24 How can social critique and emancipatory aims be incorporated into the phenomenology of the atmosphere? How can art spaces be adapted to host exhibitions on olfactory art? It is obvious that far from being complete, the aesthetics of atmosphere need to be set forth and adapted to specific fields of application, including olfactory art.

A Language of the Atmosphere

Despite the recent explosion of atmospheric studies, the possibility of relating the concept of atmosphere to contemporary olfactory art has been overlooked so far. My present approach connects these fields using analogies with the language, which appears to contradict the olfactory experience (capable of affecting a person immediately, by circumventing language and thinking) as well as the atmosphere itself (given the difficulty to put vague moods into words). Indeed, Böhme explicitly criticized the logocentrism of traditional aesthetics, with its fixation on verbal judgments and semantics, and saw in the concept of atmosphere a chance to retrieve a primarily emotional and perceptive subject. Nevertheless, I argue that the complex intertwinement between the atmosphere and olfactory art can be described in linguistic-rhetoric terms without any further general implications. In particular, when I use in the following the names of figures of speech in order to illuminate the aforementioned relationship, I do not make the claim, following Hans-Georg Gadamer’s hermeneutics, that only language can be interpreted and that whatever becomes the subject of interpretation builds a kind of language.25 My present approach neither asserts the universality of the linguistic paradigm, nor advises an ontological turn, but is guided by pragmatic reasons. In other words, linguistic and rhetorical terminology is helpful for comparing the (aesthetic) atmosphere and olfactory art, which are both still underdetermined. This weaker claim only asserts possible analogies with linguistic or rhetorical phenomena.

To start with the pleonasm, the word “atmosphere” was initially confined to the aerial layer that surrounds the Earth and it still refers to a gaseous envelope in physics.26 The air, however, is also the medium of human life and the medium of olfaction in particular; in other words, the (physical) atmosphere conditions the possibility itself of olfaction and olfactory art. Translated into linguistic terms, then, the atmosphere and olfactory art build a pleonastic pair, in the sense that whenever we speak about olfactory art, we implicitly refer to the atmosphere as well. Therefore, it would be redundant, if not tautological, to ascribe an atmospheric dimension to such artistic projects. However, this syllogism can be legitimately suspected of a certain sophistry. Indeed, the argument is related to the atmosphere as an aerial substance, whereas the aesthetic concept of atmosphere denotes the pervading mood or emotional quality of an environment. To stay with the linguistic vocabulary, physical atmospheres and emotional atmospheres are practically “homonyms.” Moreover, olfactory art – which, once again, falls under the category of fine art and is not synonymous with perfumery – to some extent does not smell at all. It is even a widespread temptation of artists to exhibit supposedly odorous items, yet their odors are de facto unperceivable or inaccessible to visitors. It would be impossible here to speculate about all the reasons behind this instrumentalization of the museal noli me tangere27 in the olfactory realm. One explanation may concern the intimate, bodily sources of the odor, especially when the flacon preserves the artist’s “essence,” but the artist’s deliberate seek and hide game cannot be excluded either. Should we suspect here the artist’s intention to protect the visitor and spare him/her unpleasant experiences or rather to tantalize him/her – or maybe both? Ambivalences are privileged by the “logic” of art.

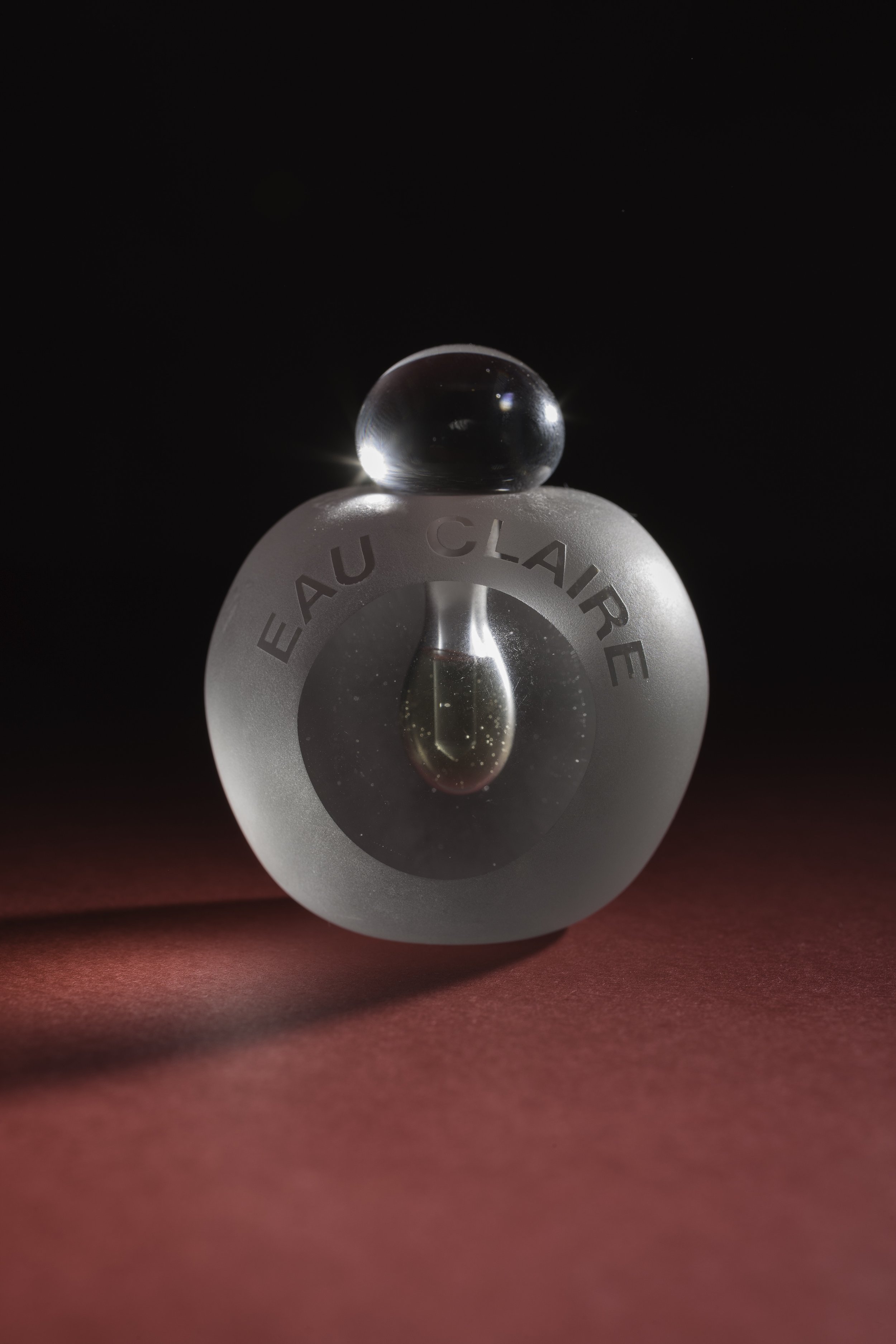

Clara Ursitt, Eau Claire, 1992-1993.

For example, Clara Ursitti distilled in Eau Claire (1992/1993) and Self-Portrait Sketch No. 2 (1995) her own body secretions, becoming one of the pioneers who transgressed this social taboo. Transferred again into the register of language, modern Western civilization imposes silence onto body odors : the ideal body is inodorous, and bodily odors are not a pertinent subject of conversation. Ursitti lets the (odorous) body speak, but at the same time she mutes this voice by closing her “essence” hermetically in a bottle. A second example is Peter de Cupere, who authored The Olfactory Art Manifest28 in 2013, exactly one hundred years after Carlo Carrà’s futurist manifesto, and signed it with his own smell. Exhibitions29 display both the printed text of the manifesto and the small bottle containing a two-year distillation of the artist’s secretions. The bottle, however, remains closed. Nevertheless, it is not so much the inaccessibility of the (presumed) odor but rather a different artistic “style” that negates assigning an atmospheric dimension to these two works. Their core is conceptual, strongly recalling Duchamp’s Air de Paris: the odorous content of the flacon can be evoked and imagined, but not perceived. At most, Ursitti’s flacon could be considered counter-evocative, as the promiscuous atmosphere suggested by the sources of smells30 is counterbalanced by the elegant visual display, in which the perfume bottle arouses associations with cleanliness, elegance and opulence. To call these works atmospheric only because they fall under the genre of olfactory art would equate with the confusion known as “false friends.” In linguistics, “false friends” informally refers to false or deceptive cognates, which are pairs of words either in two different languages, or in two dialects of the same language that have the same graphic or acoustic aspect, but differ in their meaning.31 The relationship between such words is also commonly described in linguistics as “treacherous.” It would be a “treachery” indeed to extend the notion of atmosphere to all instances of olfactory art solely because of their common reference to the air. And still, one could legitimately require an objective ground for denying the atmospheric character to Ursitti’s Eau Claire and The Olfactory Art Manifest. As a matter of fact, it is difficult to find reasonable arguments for ascribing or refuting an atmospheric quality to certain situations or environments. The feeling of atmosphere is what may be called an uncommon sense and reminds us of the Kantian judgment of taste: we expect intersubjective agreements without being able to provide verifiable or coherent reasons for our judgment. This feature, according to which the judgments about atmospheric issues are spontaneous and can (but do not have to) be subsequently explicated, is present in every atmospheric situation, be it in art or everyday life.

Moreover, today the term “atmosphere” is mostly used in a broad sense and refers to a “surrounding influence, mental, or moral environment,”32 the pervading mood associated with a place, and the aura emanated by a person. Upon closer inspection, this encompassing meaning turns out to be a dead metaphor, that is, a figure of speech whose figurative dimension is not felt anymore due to its common usage. The entire aesthetics of atmosphere is practically built upon a dead or conventionalized metaphor; the instances in which we mention atmospheres on a daily basis are completely disconnected from physics, the aerial envelope of the Earth, or the air as the medium of olfaction. Significantly enough, Böhme and Schmitz draw their examples of atmosphere primarily from non-olfactory experiences. The aesthetics of atmosphere in general seldom involves the presence of smells, and only in reference to architecture or natural environments, like in the case of Peter Zumthor and Jürgen Hasse.

Let us turn now to the olfactory art that really smells. When artists create atmospheres (in the sense of emotional spaces) with the aid of smells, they basically revive a dead metaphor and converge the two aforementioned meanings of “atmosphere” that usually function disjunctively: in these cases, it is the odor in the air that shapes a specific ambiance. From this perspective, far from being tautological, the atmospheric olfactory art represents a special case of the figurative language of smell. Such an example of reviving a dead metaphor is Meg Webster’s Moss Bed (1986, 2005/2015), which consists of a green layer of fragrant moss. The installation recalls the common wish to lie down on a bed of moss in a deep forest – a symbol of loneliness, deep rest, and clean air – but its artistic context makes this impossible. What remains for the visitor is to inhale the fresh smell of moss (which has to be regularly watered), but this enjoyable experience, too, collides with the idea that the Moss Bed may evoke in fact the grave of an unknown victim buried in the woods.

Fig. 1. Valeska Soares, Fainting Couch, 2002.

An even more penetrating natural smell emanates from Valeska Soares’ Fainting Couch (2002), which is explicitly construed upon a clash of atmospheres and sensory modalities. The image of a minimalist couch made of stainless steel, recalling a table for performing autopsies, interferes with a strong, almost narcotizing scent of lilies – flowers used at burials. These contrasting qualities – the light and cold steel on one side, the heavy floral odor on the other – and their shared morbid reference irritate and enhance the disturbing effect, producing, in rhetorical terminology, a hyperbole.

But Soares’ Fainting Couch is also a synesthetic work as are many other, if not most, objects, installations and environments belonging to olfactory art. For this reason, Shiner preferred to call olfactory works of art hybrids.33 Once more the denomination of olfactory art may generate confusion, given that olfaction functions here only as the specific difference from other artistic genres. In fact, the majority of olfactory artists are trained at conventional art academies and integrate odors into multisensory compositions. Therefore, to subsume their works under the label of olfactory art resembles a pars pro toto operation; using again an analogy with rhetorical tropes, the concept of olfactory art conceals a synecdoche, as when perfumers are called “noses.”34

Let us take another example: Peter de Cupere’s Stay Awake (Coffee Room Installation), commissioned by the Städtische Galerie Bremen (Germany) for the exhibition “Olfaktor. Geruch gleich Gegenwart” (2021), and exhibited in the @thee.drops exhibition space. While the title conceals an anticolonial message related to the working conditions on African coffee plantations in former Belgian colonies, the subtitle acts as a descriptive functor: the installation is literally a room covered with coffee beans and ground coffee. Peter de Cupere’s work is not merely about coffee, but it transports a meaning through the material of coffee as a medium. At the very opposite of the conceptual “wing” of olfactory art, his Coffee Room (along with his Smoke Room, also displayed at the Städtische Galerie exhibition) epitomizes the symbolic power of materials and illustrates the recent scholarly turn towards the aesthetics of materiality.35 The installation Stay Awake confirms the rule of “hybridity” (Shiner) or synesthesia: the back of the room displays chains next to coffee bags with Africans’ heads coming up from them. From there, mysterious footsteps lead to the table and chair in the middle of the room, which are also covered with coffee beans, as well as a coffee pot on the table. The visitor feels that the smell of coffee is almost perspiring from this cave-like space. In the previous room, if the visitor presses the foot pump at the base of a white uncovered pedestal, the smell of sweat is emitted, suggesting the slaves’ fear and physical exhaustion. Stay Awake has a double message; the invigorating effect of coffee is ambiguously mixed with the reminder of the cruel exploitation that made possible the enjoyable comfort of the bourgeoisie, as well as their greed. One can even decipher allusions to Goya’s “the sleep of reason produces monsters” and to the Freudian return of the repressed: the colonizers would gladly forget their crimes, but the memories of their victims haunt their dreams or pop up in private dining rooms. The entire colonial nightmare is evoked with one simple material— coffee—and one invisible medium—odor. A powerful atmospheric quality is masterfully achieved through artistic minimalism. Stay Awake (Coffee Room Installation) therefore combines not only the polysemy of metaphors with literal descriptions, but it also operates with multiple, successive synecdoches, by substituting the abstract whole (the colonialist regime) through a concrete part (coffee plantations), the object (coffee plantation) through its material (coffee), and finally the material (coffee) through its effect (keeping awake).

Work Titles and Exhibitional Discourses

Looking back, it seems that the same blood, so to speak, flows through the veins of the atmosphere and olfactory art, both sharing the medium of air; olfactory art is in principle based on breathing and presupposes the subject’s corporeal immersion in the physical atmosphere. However, in practice, olfactory art and atmosphere rather behave like communicating vessels, and it is necessary to differentiate between various cases, such as non-odorous atmospheres in art (when ambiances are created solely with audiovisual means), non-atmospheric odorous art (mostly in conceptual art, in which emotional atmospheres and olfactory art behave like “false friends”), and atmospheric more-than-olfactory art. The various concepts of atmosphere and art (olfactory art in particular) are therefore overlapping. When artists evoke moods with the aid of specific odors, an ambiguous situation emerges in which the “aura” of such works can be partly explained by the intricate connection between smells, emotions and environments which have engulfing qualities.36 Despite the aforementioned rejection of the logocentric paradigm by the founders of the aesthetics of atmosphere, and the estrangement that analogies using rhetorical terminology may make, the comparison between olfactory art and figures of speech can help us see works of olfactory art in a new light and to structure this extremely heterogeneous field of practices. Moreover, the loans borrowed from linguistics can even be extended, so let me provide two more aspects that deserve closer scrutiny on another occasion.

The first one has already been touched upon and concerns the direct use of language and figures of speech in the olfactory art. Unarguably, as Moss Bed and Stay Awake have shown, the titles of the olfactory works often play with the language, like all the other artistic genres. In addition to the titles, olfactory artists integrate language into their works by writing manifests and other programmatic texts, like de Cupere, or by inviting visitors to pay attention to their daily olfactory experiences and describe them, like in Anne Schlöpke’s Smell diary (Städtische Galerie Bremen, 2021). Other artists count on the force of synesthetic associations. Svenja Wetzenstein’s interactive installation Gedanken-Duft-Labor (Weserburg Museum für moderne Kunst Bremen, 2021) is presented as “a sort of word-factory”: visitors are invited to combine words, colors, and olfactory representations in order to produce new words and develop surprising combinations of (again imagined) odors. Imagination is also required for interpreting the work of Bernard Lassus, who installed a plate in a park with the words, “If west-wind, chocolate mousse”; one can detect the smells coming from a nearby confectionery factory under certain weather conditions.37 In this case, language itself becomes a poetic strategy for minimal artistic interventions in the open air.

Another domain in which analogies with the verbal language are promising regards the spatial arrangement of exhibitions in general. The visitor is invited to follow a certain route to view the displayed works, which are numbered. In L’Invention du Quotidien. Vol. 1. Arts de faire (1980), Michel de Certeau defined walking as a space of enunciation and unraveled its narrative structure; walking “acts-out” the (abstract) place and opens a (lived) space in a similar way to the spoken parole or the speech act that instantiates the system of the langue. He asserts: “The act of walking is to the urban system what the speech act is to language or to the statements uttered. At the most elementary level, it has a triple ‘enunciative’ function: it is a process of appropriation of the topographical system on the part of the pedestrian (just as the speaker appropriates and takes on the language); it is a spatial acting-out of the place (just as the speech act is an acoustic acting-out of language); and it implies relations among differentiated positions, that is, among pragmatic ‘contracts’ in the form of movements (just as verbal enunciation is an ‘allocution’, ‘posits another opposite’ the speaker and puts contracts between interlocutors into action).”38 Architects and urban planners create stable structures (or language, in Certeau’s approach) that invite or suggest citizens to follow particular routes (that is, to utter statements), yet without prescribing them; pedestrians have to act them out and still have alternative options. In a museum, too, on one hand, the curator’s choice in arranging the exhibits creates a spatial and temporal order through both juxtaposition and logical or chronological sequences; in so doing, the curator, whether deliberately or not, produces a discourse that productively guides the visitor’s experience and induces certain interpretations, making others less probable. On the other hand, the visitor has to actuate a route and can modify the suggested order. Itineraries through an exhibition form discourses or, in Certeau’s words, “a conjunctive and disjunctive articulation of places,”39 by unifying separate positions in space and possibly leaving others out. Nevertheless, whereas the interpretative key adopted by the present paper is focused on stylistics, an analysis of the placement of exhibited items would be better served by references to syntactic structures, even though Certeau himself ascribed a “rhetoric of walking” to the pedestrian.40 From this perspective, an exhibition might be regarded as a phrase with one idea that is summarized in the main sentence and elaborated, varied, or completed in the secondary sentences, or as a set of equally important strings that resemble coordinated sentences. However, this interpretation concerns the curatorial work in general, not only olfactory art. Returning to olfactory art, it is time to explain in which respect it can be considered an idiolect of the atmosphere.

The Idiolect of the Atmosphere

The concept of idiolect in linguistics refers to the language of an individual and is related to his/her personal expression.41 As such, it is restricted to a person’s linguistic output and to a certain period of time. This means that a speaker can make use of various idiolects in different stages of life and that s/he can even master at least two different idiolects at the same time. In any case, specificity is an essential aspect; the idiolect comprises the variations and stylistic features which distinguish a speaker’s language from another’s belonging to the same dialect. Obviously, the concept of idiolect cannot be employed in its standard meaning in the case of olfactory art, because the physical atmosphere is neither a person nor a speaker. It is language again that provides the answer: idio- from the Greek meaning private and personal, but also peculiar and distinct; and logos referring to language and a certain order or “logic.” Keeping this in mind, the constellation of expressive patterns of olfactory art can be regarded as building a specific “language” of the atmosphere. Other art forms, such as music or film, are also able to create emotional atmospheres, but with other expressive means, that is to say, by resorting to distinct idiolects. Olfactory art is not necessarily more apt than other arts to evoke (emotional) atmospheres only because it shares the medium of air with the physical atmosphere. The expressive diversity of atmospheric art is set forth within the same idiolect, as I have argued with the examples of olfactory art. It would be difficult, if not impossible, to reduce this rhetorical variety of olfactory art to a common feature; on the contrary, we might discover further figures of speech if we were to consider more artistic examples. Ultimately, this entire examination emphasizes the openness of artistic practices and raises doubts about the legitimacy of normative approaches coming from philosophical aesthetics. To give one single example for the latter approach: Siegfried Krakauer’s “fundamental aesthetic principle” says that the more an individual work of art takes into consideration the specific properties of a certain medium, the more satisfying its performances can be and, conversely, if a work contradicts the essence of its medium, producing, for example, effects that would better correspond to another medium, it risks its aesthetic quality.42 However, my analysis demonstrates the impossibility of reducing the perceptual medium of smell to an “essence” that would subsequently serve as a guiding thread for the evaluation of individual works of olfactory art. The production of ambiances is only one possibility, but contemporary artists continue to show how odors can be employed using false cognates, dead metaphors, hyperboles, synecdoches, metaphors and other possible figures of speech in innumerable ways.

❃ ❃ ❃

Madalina Diaconu is Dozentin for philosophy at the University of Vienna. She is a member of the editorial boards for Contemporary Aesthetics, polylog. Zeitschrift für interkulturelles Philosophieren and Studia Phaenomenologica. She has authored ten books and (co)edited eleven collective volumes on the phenomenology of senses, the aesthetics of touch, smell and taste, urban sensescapes, sensory design, and environmental philosophy. In 2021 she co-curated the exhibition “Olfaktor. Geruch gleich Gegenwart” with Ingmar Lähnemann at the Städtische Galerie Bremen.

- Larry Shiner, Julia Kriskovets, “The aesthetics of smelly art”, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 65:3 (Summer 2007), 282.

- Larry Shiner, Art Scents: Exploring the Aesthetics of Smell and the Olfactory Arts, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

- For example, Max Ryynänen interprets the Indian rasa theory as a proto-aesthetics of the atmosphere, Takao Aoki detects affinities between atmosphere and the preference for vagueness of the Japanese culture, and terminological difficulties arise in translating the concept of the atmosphere into Chinese (Max Ryynänen, “Rasafication: The Aesthetic Manipulation of our Everyday”, The Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics 2019/1 (Spring), vol. 42, 165–169; Takao Aoki, “On the Aesthetics of Haze or Obscurity”, lecture at the 21st International Congress of Aesthetics, Belgrade, 24.07.2019).

- Friedrich Otto Bollnow, Die pädagogische Atmosphäre. Untersuchungen über die gefühlsmäßigen zwischenmenschlichen Voraussetzungen der Erziehung, Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer, 1964.

- Hubert Tellenbach, Geschmack und Atmosphäre. Medien menschlichen Elementarkontaktes, Salzburg: Müller, 1968.

- Hermann Schmitz, System der Philosophie III.2. Der Gefühlsraum, Bonn: Bouvier, 1969.

- Gernot Böhme, Atmosphäre. Essays zur neuen Ästhetik, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1995.

- Gernot Böhme, Aisthetik. Vorlesungen über Ästhetik als allgemeine Wahrnehmungslehre, München: Fink, 2001.

- Christiane Heibach, „Einleitung“, in Atmosphären. Dimensionen eines diffusen Phänomens, ed. by Christiane Heibach, München: Fink, 2012, 9–23.

- See the book series “Atmospheric Spaces” with Mimesis International. link.

- Tonino Griffero, Atmospheres: Aesthetics of Emotional Spaces, Farnham: Ashgate, 2014.

- Rainer Kazig, Damien Masson, Daniel Siret, “A few words about the International Ambiances Network”. 3rd International Congress on Ambiances “Ambiances, tomorrow”, Sep. 2016, Volos, Greece, 29–36, https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01428779/document [31.08.2021].

- This is how Gernot Böhme labeled the new stage of capitalism in which utility (Gebrauchswert) tends to be replaced by design and presentation (Inszenierungswert) (Ästhetischer Kapitalismus, Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2016).

- Peter Sloterdijk, Bubbles. Spheres vol. I, Globes. Spheres vol. II, Foams. Spheres vol. III, all three translations published with Semiotext(e) in Los Angeles in 2011, 2014, and 2016.

- Hartmut Rosa, Resonanz. Eine Soziologie der Weltbeziehung, Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2016.

- Tellenbach 1968: 56.

- Hermann Schmitz, Atmosphären, Freiburg, Munich: Alber, 2014, 69 [my transl., M.D.].

- Griffero 2014: 5.

- Böhme 2001: 46–58.

- Ibid.: 59–71.

- Cf. also Griffero 2014: 120.

- On the concept of Patheur see Jürgen Hasse, Was Räume mit uns machen – und wir mit ihnen. Kritische Phänomenologies des Raumes, Freiburg, München: Alber, 2014, 45 .

- Peter Zumthor, Atmospheres. Architectural Environmental, Surrounding Objects, Basel, Boston, Berlin: Birkhäuser, 2006.

- Gerhard Schulze, Die Erlebnisgesellschaft: Kultursoziologie der Gegenwart, Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 2005.

- Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, New York: Crossroad, 1992.

- Madalina Diaconu, Tasten, Riechen, Schmecken. Eine Ästhetik der anästhesierten Sinne, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2020, 442.

- Latin for “Do not touch me!”. These words were attributed to Jesus when he met Mary Magdalene shortly after his resurrection and gave the title to several works of the Italian Renaissance depicting this moment. This sentence refers here to the interdiction to touch the exhibits in museums, which inspired among others Marcel Duchamp’s Priére de toucher (1947).

- www.olfactoryartmanifest.com [1.09.2021]

- E.g. “Belle Haleine” in Tinguely Museum in Basel (2015), “DUFT, SMELL, OLOR, … Multiple Darstellungen des Olfaktorischen in der zeitgenössischen Kunst” in Weserburg Museum für moderne Kunst in Bremen (2021).

- This information is not in the caption, but is mentioned by guides and reviewers.

- Richard Nordquist, “What Words Are False Friends?” ThoughtCo, Aug. 27, 2020, thoughtco.com/false-friends-words-term-1690852 [31.08.2021].

- “Atmosphere”, Online Etymological Dictionary, etymonline.com/word/atmosphere [31.08.2021].

- “A complicating factor in the case of olfactory art is that most olfactory works are hybrids that either use odors to enhance traditional fine art forms like drama, film, and music or else integrate odors into multisensory installation, performance, or participatory pieces.” (Shiner 2020: 146)

- The synecdoche refers to a figure of speech in which the whole represents a part or vice versa, or the matter stands for the object. This is the case when composers of perfumes are currently called “nez” (French for ‘nose’). This implicit or explicit synesthetic dimension has far-reaching implications for the understanding of visual arts in general, including the non-visual qualities of painting and sculpture.

- Christiane Heibach, Carsten Rohde (eds.), Ästhetik der Materialität, Paderborn: Fink, 2015.

- In this respect Tellenbach calls the atmosphere das Umgreifende (Tellenbach 1968: 56).

- Bernard Lassus, Couleur, lumière … paysage: instants d’une pédagogie, Paris: Monum, Éd. du Patrimoine, 2004.

- Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, Berkeley. Translated by Steven Rendall. Los, Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1988, 97-98.

- Ibid.: 99.

- Ibid.

- K. Hazen, “Idiolect”, in Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, ed. by Keith Brown (Editor-in-Chief), second edition, vol. 5, Oxford: Elsevier, 2006, 512–513.

- Siegfried Krakauer, Theorie des Films. Die Errettung der äußeren Wirklichkeit. Werke Bd. 3, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2005, 27–59.

Suggested Reading