What Might Not, Might Last

Mary Ann Caws

“Surely the bubbles do just that, they transport us beyond where we normally reside, and they make concrete the kind of magic in which Cornell so firmly believed… a pure and evanescent world indicative of another far beyond.”

Volume One, Issue Two, “Air Bubbles,” Essay

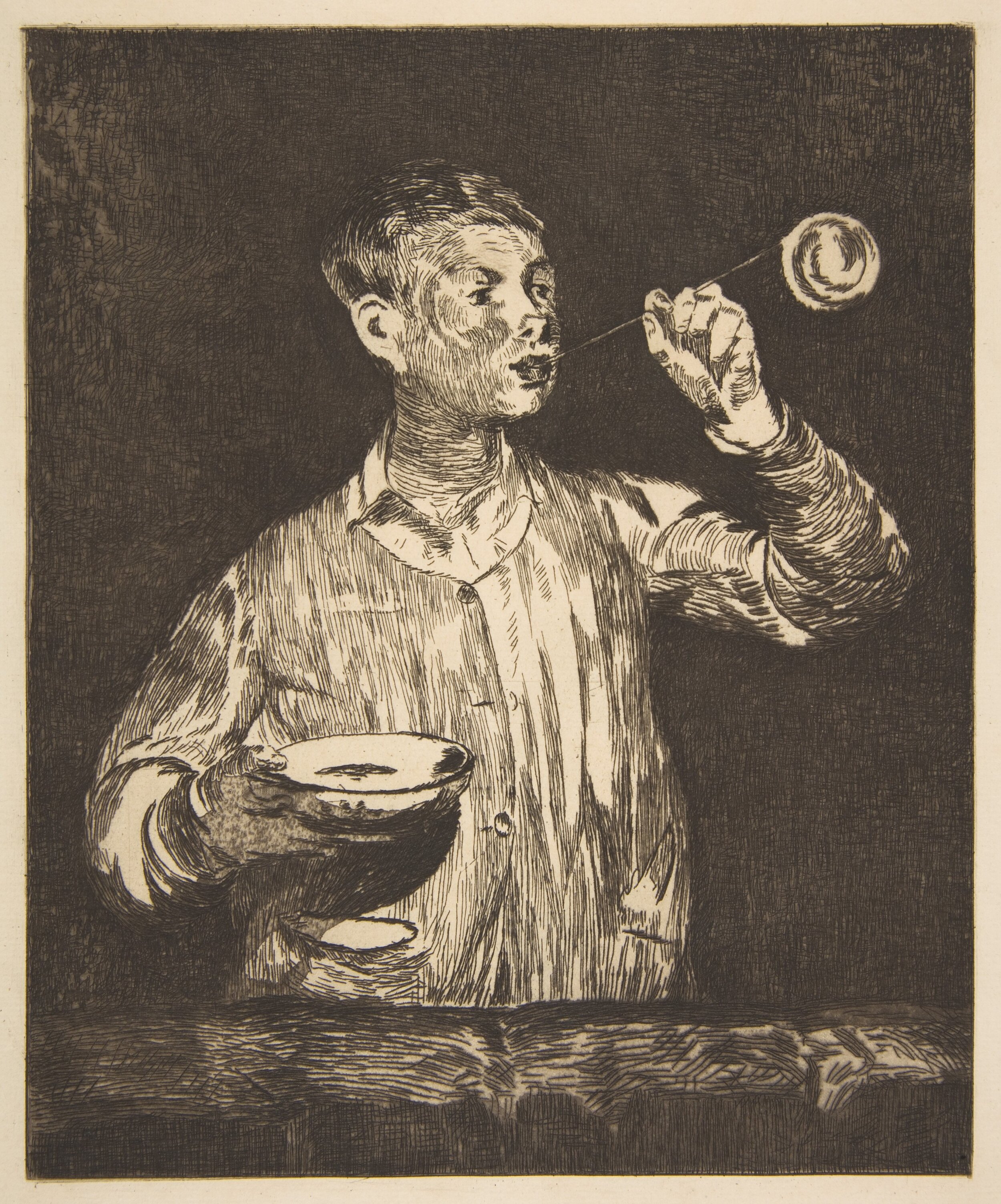

Édouard Manet, Boy with Soap Bubbles, 1867-69, Etching, lavis aquatint, and roulette on laid paper, second state of four, from 1905 Strölin edition, Rogers Fund, 1921, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain, Source.

The etching shows Léon Koelin-Leenhoff, thought to be Manet’s illegitimate son with Suzanne Leenhoff, the artist’s piano teacher whom he later married. Whether such biographical information can be used to effectively “interpret” a work of art such as this is frequently debated by art historians. However, the curl of light on the bubble is echoed around the boy’s right eye, transposing some of the bubble’s delicate fragility onto him, suggesting a fatherly gaze. Similarly, light patterns are repeated in the main figure of Chardin’s Soap Bubbles and the bubble that he blows; it is with this painting that Mary Ann Caws begins her article. Bubbles, she states, are always somewhat about hoping. Using biographical information about Joseph Cornell — his Christian Science practice and belief in white magic — Caws traces the affects we associate with bubbles in the artist's shadow boxes.

- The Editors

A Bit of History

When I first started thinking about bubbles and the blowing of them, the Chardin image of 1734 in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., called Soap Bubbles, swept me up entirely. Here was a deeply concerned man leaning over a window ledge, with a natural image of a tree branch overhead, his concentration itself being a thing of beauty. Here were leaves above and beneath the window, and his intensity is doubled by the adorable child to his left, observing the magic of the bubble. The liquid, like soap, to his right, his hands gracefully placed one above the other, his hair as beautifully arranged as the picture itself. For that lock of hair, ending with a curl, echoed by the child’s hat, whose (as it were) feather reaches over, like the man’s hair, copying that natural if human item. All imitation, all joyful elegance, and all concentrated on the development of an optimistic vision, a bubble blower, bubble blown, and observer of the scene, of the creative gesture. This to me is the perfect concentration of the natural and the constructed to be observed: of all things, a window of the familial and the art inventiveness, so that the vision of the bubbles could spread into the world beyond.

“This to me is the perfect concentration of the natural and the constructed to be observed: of all things, a window of the familial and the art inventiveness, so that the vision of the bubbles could spread into the world beyond.”

Jean Siméon Chardin, Soap Bubbles, 1734, Oil on canvas, Gift of Mrs. John W. Simpson, National Gallery of Art, Public Domain, Source.

All that, of course, and here’s an odd thing. I am thinking, as I often do, of a beloved artist — a painter, no, an artist, just before our time, depending on our age, or way before, but still in the twentieth if not yet the twenty-first century: Joseph Cornell, himself obsessed with ritual, that of the Christian Science celebrations on Wednesday night, was no less concerned by the transparency, the ethereality of the soap bubble. These for him, as I see it now, made visible the transparency of that other world in which he so often lived, the world of Christian Science. Something, then, beyond our normal way of being.

I am speaking here from my own experience of Science in that sense, dating from long ago. I grew up in Wilmington, North Carolina, where Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science and author of its major work, Science and Health and the Key to the Scriptures, (which you can consult in any of the Christian Science Reading Rooms) spent a night or several, as announced on a plaque on Front Street, the town’s major street. When I spent a year abroad from Bryn Mawr College in Paris, my roommate was a Christian Scientist from a family that adhered to its doctrine, as did she. If you were sick, as she turned out to be sometimes, you phoned the practitioner and explained the symptoms, which were, in principle, talked away or prayed away over the phone. Luckily, there was one of those in Paris, so the phone calls were not too expensive. Elsewhere, for example, in Aspen, Colorado, where Mina Loy the poet and painter (also a Christian Scientist) went to live the last years of her life, there was not one, and so the phone calls back to New York — where the Scientist she was in touch with was living — were ultra-dear. So, her daughter Joella, because of whose early leg paralysis Mina had entered the Christian Scientist flock, sometimes pretended to be that person to whom her mother needed to speak.1

In Paris, the French lady with whom we lived during that year was a believer in Roman Catholicism and would have a priest come and sanctify the room from which my roommate would make the call. And still in Paris, I would play the piano at the Christian Science Church, whereas later and here in New York, I now walk by the Church, built in 1921, on 9 East 43rd Street on Wednesdays and sometimes go in for a moment and read the Science material. For years, I was editing the papers and files of the box artist Joseph Cornell, very much a believer. When I wanted to publish his letters to his deceased mother and brother, I had to receive permission from the Mother Church in Boston to do so. Thus, I absorbed a bit of that thinking, in which the belief in the real is modified by a kind of Other Perception, to me a kind of bubble universe.

So let me say that the very fragility and see-throughness of the miraculous object — too visionary and see-through-visible to be called by such a heavy term visibly and orally as “bubble” — takes us through much. The soap component or whatever permits the blowing out of the bubble, as in the Chardin painting, is part of the essential sensed purity of the vision. This is crucial, for in art, in life, and whatever else there might be — once you open the air and the bubbled air, you have let all the genies or ghosts emerge.

Writing (in) a Bubble

Asked to write this piece for the journal Venti (wind, air, and I am sure, in some to be cases, Hot Air), I am dealing superficially and so airily, I guess, with it all, or part.2 Necessarily, it will happily disappear, since any whole piece I now read as a writer reads her own writing, as being itself much of a bubble.

I am seeing, even as I write, something trivially up there in the ether, taking just the time I am taking right now to reflect upon it. I have chosen to envision the air bubbles in the boxes of Joseph Cornell — known for imprisoning his favorite nineteenth-century ballerinas and singers, those stars of the past, in boxes he would construct rapidly and treasure, even as he gave them away. A wonderful anecdote, and this too reads as sufficiently airy to be worth re-citing. (Yes, I heard me write “re-citing,” as if I were re-hearsing, or re-hearing with a rattlecall of the death chariot within my words and remembrance of those surrealizing early films like Satie’s and Picabia’s Entr’acte or the very great Relâche, in its humorous self-undoing, as it brings along its meta-meaning of the theatrical “closed now,” and I will end here my parenthesis.)

Surely the bubbles do just that, they transport us beyond where we normally reside, and they make concrete the kind of magic in which Cornell so firmly believed, not that dark magic of the surrealists with its suspicion for him of a kind of evil presence, but a pure and evanescent world indicative of another far beyond. A healing world, so that the bubbles for him signified the healing process, the essential goodness in which he so devotedly believed, that kind of performance of magic he followed with passion.

Like smoke rings, the far other side of the natural, each mutation perhaps wishes for the same informality and purity and transparency. Something about the bubble is always about hoping, breathing, being. It is a remarkable image of perseverance. Of course, the very real danger from without is somehow reflected by the worry from within: bubbles are, by their nature, not meant to last. They contain their own vision, but they reflect, on their surface the outside: so, they are the perfect illustrations of without and transparently both: you can see one through the other.

Created as if it were a real art, the act of blowing the bubbles that remain in globe shape is in many of Cornell’s boxes and games and frames. There, we can play with a roll of dice or a game-shaped ball — essentially for play, but no less for thought. For with them, we learn to roll along, to roll up and gather from below. What could be more good magic than a game in which a form infinitely fragile becomes an enduring piece, in a deeply literary and visual conundrum? It can be rolled along a wire, or tossed in the air or blown away. And the innocence of the game persists: we know how Cornell believed in white magic, and the bubble is supremely magical in its enduring or collapsing. It is multiple and magical.

“So, the Soap Bubble Set of 1949-1950 in the Smithsonian Museum is perfect in its illustration of the impermanence of the thing. The glass cup at the lower left is broken, and from it the bubbles will arise, indicating their whole life cycle: the blowing up of the air and the destruction of even the container of possibility.”

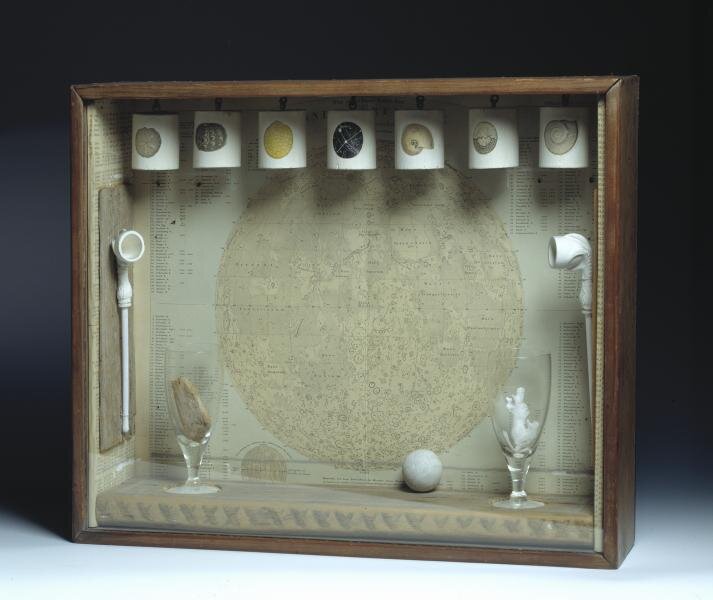

Joseph Cornell, Soap Bubble Set, 1949-1950, glasses, pipes, printed paper, and other media in a glass-fronted wood box, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase made possible by the American Art Forum, 1999.91, Source.

So, the Soap Bubble Set of 1949-1950 in the Smithsonian American Art Museum is perfect in its illustration of the impermanence of the thing. The glass cup at the lower left is broken, and from it the bubbles will arise, indicating their whole life cycle: the blowing up of the air and the destruction of even the container of possibility. Meditating on the outside of the globe and that perfect circular containment is like looking at the outside of a world, complete in itself and, for that perfection, a threat to both its surroundings and its inward vision, so tightly bordered and such a refusal of anything not itself. What could thrive in this airlessness which is also complete? The perfection of the bubble in the long run is its undoing — its intense airlessness cannot express anything but itself, its own hemming in of existence. The irony of Cornell’s Pharmacy Series, with the bottles promising relief from normalcy, is that it is in fact an anti-life series, for nothing can be added to those shapes.

Quote from wall panel of this Soap Bubble Set from 1949-50:

Soap Bubble Set offers a theatrical glimpse into the cosmos. Situated on Earth, the viewer observes the mountains and valleys of the moon, first discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610. The glasses, holding specimens of land and sea, embody the gravitational pull of the earth, perhaps in relation to the lunar influence on tides. The freely moving sphere rolls between the opposing forces while cutouts of shells, stars, and other references to the natural world float above. Following Edwin Hubble’s confirmation of the rapidly expanding universe in 1929, the metaphor of a swelling soap bubble proliferated in the popular press. For Cornell, who had a long-standing interest in astronomy and stayed abreast of breaking news, this metaphor would have resonated with his own memories of blowing bubbles with clay pipes as a child and the wonder of their creation. Cornell’s series of Soap Bubble Sets, sometimes called planetariums, is a decade-long rumination on the great astronomers of the past and the contemporary discoveries and innovations in space technology.

But here is the play of the bubble as I focus my gaze again: the cup is in no way broken, I just could not see the top of the left glass for one of the insertions described as the “specimens of land and sea,” and its position against the pale backdrop. So, let me revise my point of view. The small globe at the bottom has, of course, the shape of the bubble, making it a global conception indeed, as if the magic of the airy construction were to be mirrored, no, compacted into the small space. And here is the other side of the misconception that was my initial entry into this box: brokenness would have been a dark side of the surrealist viewpoint, whereas Cornell's entire way of imagining desired only the white magic, that which had no black magic to it. Thus, the purity of the soap bubble, whose conception was also its spiritual many-sidedness — in honor of which there are at the top what the panel describes as “cutouts of shells, stars, and other references to the natural world” which are indeed floating above. “The freely-moving sphere” rolls between those columns or pillars at the box sides, which are themselves pipes, the architects of the entire construction, so that the universe of this box is itself a world gone globular or global.

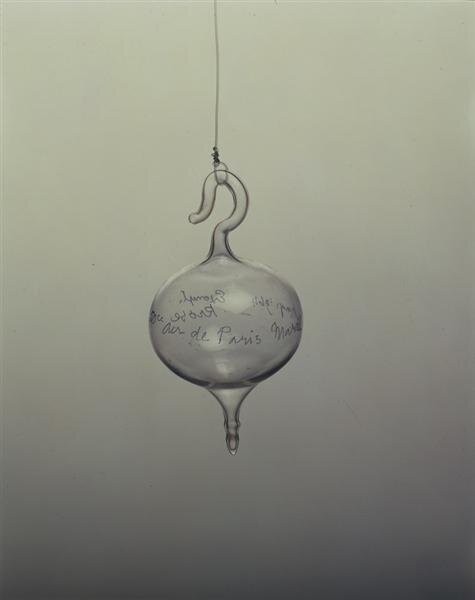

As Duchamp’s Air de Paris in its glass vial cannot be changed or breathed, the bubble can only be broken, like a toy balloon. How to not desire (as in surrealism, the Art de Désirer is what is meant to last), the Air de Paris of Marcel Duchamp, with that air treated as precious and preserved in a tiny crystal space, no harm to it?

“When we contemplate Marcel Duchamp’s Air de Paris, enclosed straight from Paris in a tiny woven glass bubble, that capture of French atmosphere, paradoxically opens up as much as we could now desire. This returns us to the whole scale of possibilities: the birth, the development, and the desire for completion.”

Marcel Duchamp, 55 cc of Paris Air, 1919, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Public Domain, Source.

The Other Side of the Thing

About Marcel Duchamp, in a way, and not just a small way, given his salute to the urinal and to art in his chamber music of a Fountain as a Parisian piss pot on exhibition — not only mocking the art man — there is a fine small book entitled Duchamp's Last Day.3 What a brilliant, if breathily “trivial” subject, and perhaps such a writing is, not just was, the best way to celebrate not just air but art, in something so slight, as that air of Paris was slight, and something so meaningful as that gesture. Here in New York – so beleaguered — when we contemplate Marcel Duchamp’s Air de Paris, enclosed straight from Paris in a tiny woven glass bubble, that capture of French atmosphere, paradoxically opens up as much as we could now desire. This returns us to the whole scale of possibilities: the birth, the development, and the desire for completion.

Let me, in closing this slight piece, salute the not entirely forlorn hope that the open air might someday bring to this country, a responding Air de New York. And then the possibilities are immense: the containment of Paris or anywhere else in that Marcel shape, and, before that, the containment of whatever vision we might want to include in our own visions, knowing they will not last.

❃ ❃ ❃

Mary Ann Caws is Distinguished Professor Emerita of Comparative Literature, English, and French at the Graduate School of the City University of New York. She is an Officier of the Palmes académiques, a Chevalier dans l'ordre des Arts et des Lettres, holds a Doctor of Humane Letters from Union College, is the recipient of Guggenheim, Rockefeller, and Getty fellowships, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the past president of the Modern Language and Literature Association and of the American Comparative Literature Association. She is the author of The Eye in the Text, The Surrealist Look: an Erotics of Encounter, The Modern Art Cookbook, Blaise Pascal: Miracles and Reason, Creative Gatherings: Meeting Places of Modernism, a translator of Mallarmé, Char, des Forêts, Reveredy, Breton, Desnos, and the editor of HarperCollins World Literature, the Yale Anthology of Twentieth Century French Poetry, The Surrealist Painters and Poets, and Milk Bowl of Feathers: Essential Surrealist Writings, and the forthcoming Alice Paalen Rahon (poet series, NYRB) and co-editor of French Prose Poems (NYRB).

- Thinking from my forthcoming book: Mary Ann Caws, Mina Loy, Critical Lives (London: Reaktion Books, 2020). ↩

- I am thinking here of the HOT AIR which was playfully used as a title for the lunches of the artists frequenting the amazing Florence Griswold House in Old Lyme, Mass., which has a chapter in my Creative Gatherings: Meeting Places of Modernism (London: Reaktion Books, 2019). They lunched on the porch and told wonderfully long tales. As this piece might feel, even as I write it. ↩

- Donald Shambroom, Duchamp’s Last Day, Ekphrasis series (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2018). ↩